Genetic algorithms take inspiration from biology to solve difficult problems. A population undergoes selection, competition, cross-breeding and random mutation to produce the next generation. After iterating over many generations, the entire population becomes closer to optimum, however you define that.

In this, the population is pictures made of 500 triangles, and optimum means: get as close as possible to this picture that i took recently in Skanderborg:

I know i’m at least 15 years late to this game, but i’ve always wanted to try it, so i suddenly just decided to give it a go.

Initial population

I started off by generating 100 random images, each using 500 random triangles.

Selection

Selection, akin to “survival of the fittest”, means that not all images survive infancy. I decided to judge fitness using a mean squared error (MSE) algorithm comparing each image against the target image. The algorithm returns a number: the lower the number, the closer it is to the target image.

At this stage, all of the images are far from ideal, but some are slightly better than others. I decided to rank them all by fitness and eliminate half of the population.

Competition

The next step is competition, choosing parents to make the next generation.

You can just pick parents at random, but i found that a tournament gave better results.

For each tournament, i selected 5 images at random, and the strongest one wins. I did this several times to pair up parents to make children for the next generation.

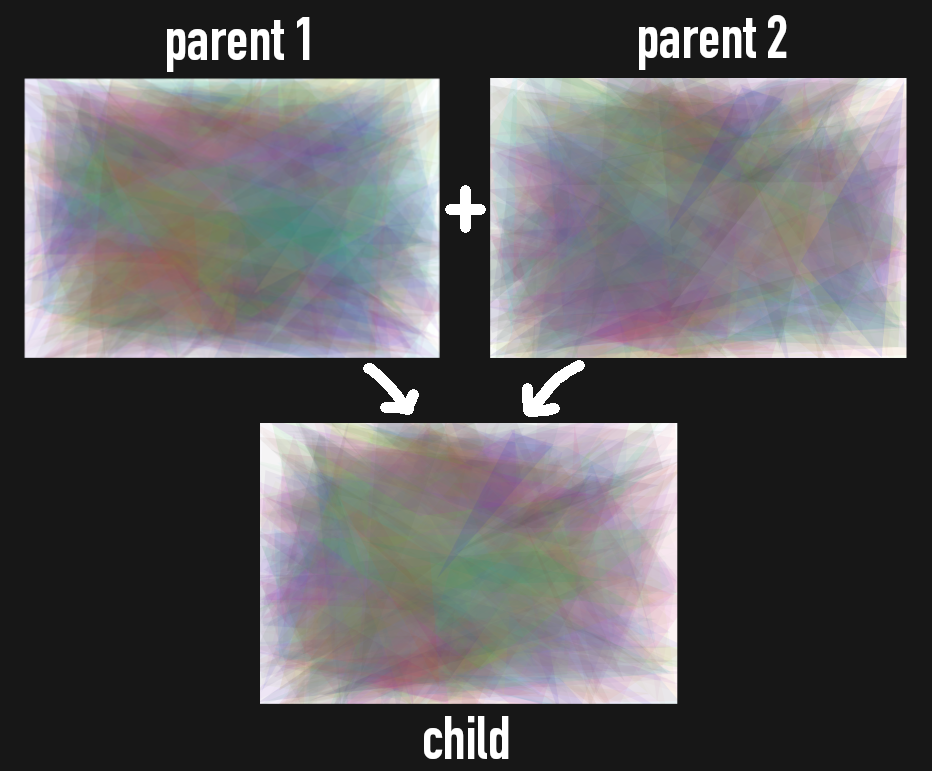

Cross-breeding

This is the fun bit, and what makes this method really feel like genetics.

You can consider the 500 triangles as a strand of DNA. In cross-breeding, i took a selection of triangles from each parent.

Here’s an example of what that looks like:

It’s nice because you can see visually that the child contains some elements from each parent.

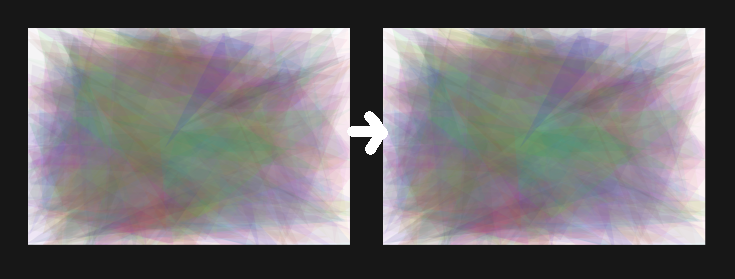

Mutation

Mutation mimics the random changes in DNA that help a population gain advantages over time.

For each child image i take a few triangles and adjust them a little bit. Either move the corners slighty, or adjust the colour a little bit, or remove it entirely and create a whole new triangle.

Here’s an example of what mutation can look like:

If it’s hard to see the differences, try comparing in new tabs:

before-mutation.png, after-mutation.png

I found a variable mutation rate works well. At the beginning you can gain a lot with a high variation, but as the picture gets closer, the mutation rate needs to be smaller. If you change too much, you might improve one thing, but lose it by changing too many other things that aren’t helpful.

Repeat for 10000 generations

I continued selecting, competing, cross-breeding and mutating for 10000 generations.

It’s really fascinating to see how a process like this slowly nudges the entire population in the direction of a desired result, and a picture slowly emerges out of the random noise.

Here was the best image after 10 generations, still pretty random:

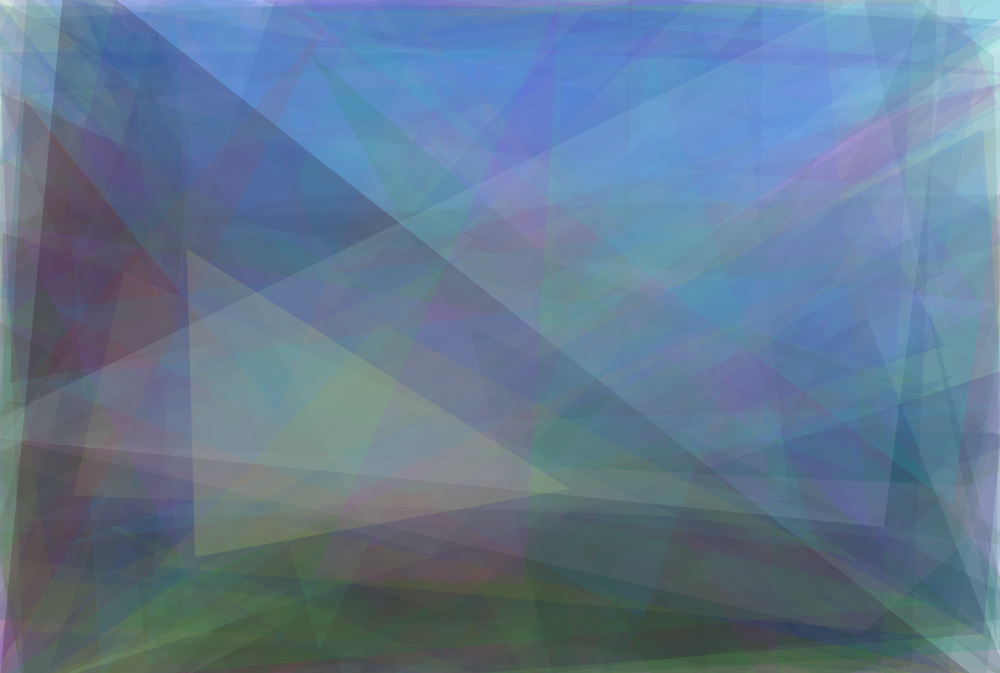

By generation 100 you can start to see the colours getting closer to desired, and a ghostly impression of the boat begins to emerge:

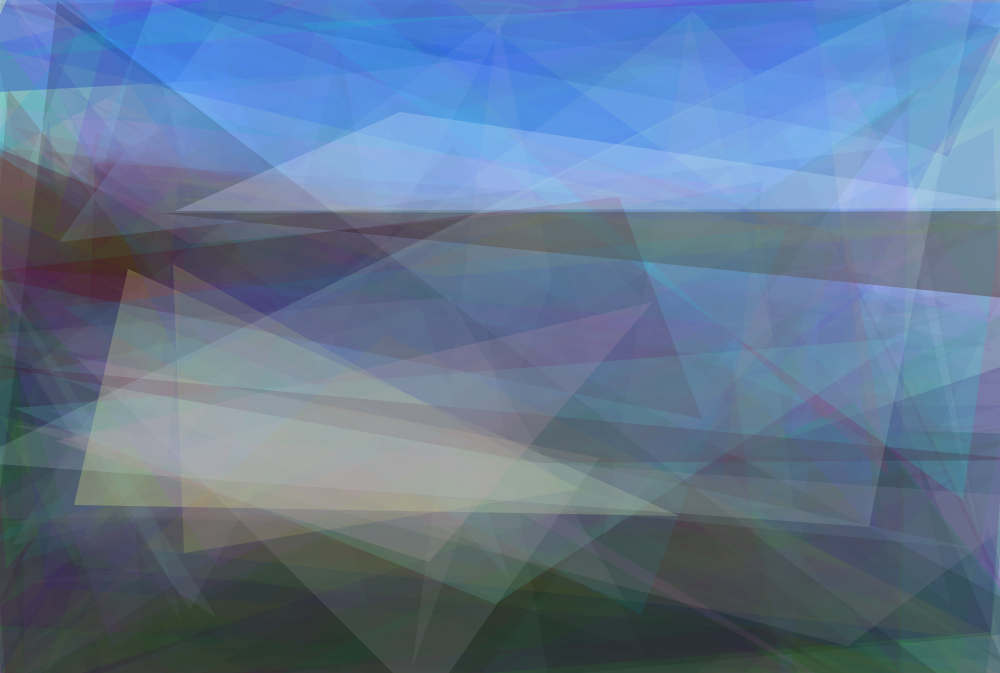

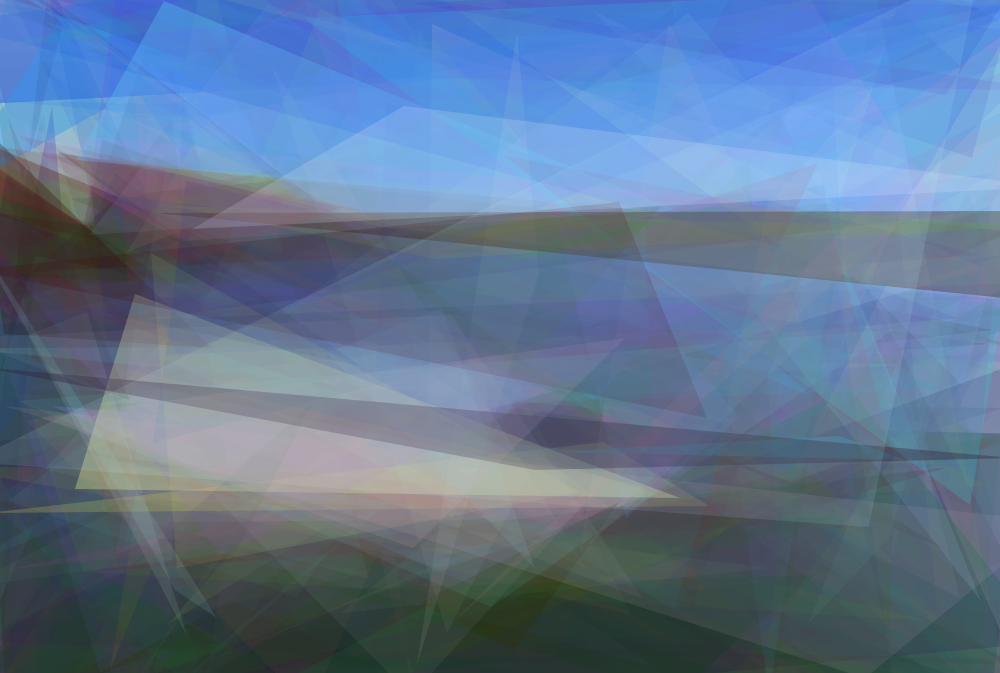

By generation 1000 the boat is getting clearer, and there is a distinction of sky and lake:

The diminishing returns means that generation 10000 isn’t all that much different, but if you look from a distance and squint your eyes, you can kind of imagine you’re in Skanderborg!

What i learned from all of this

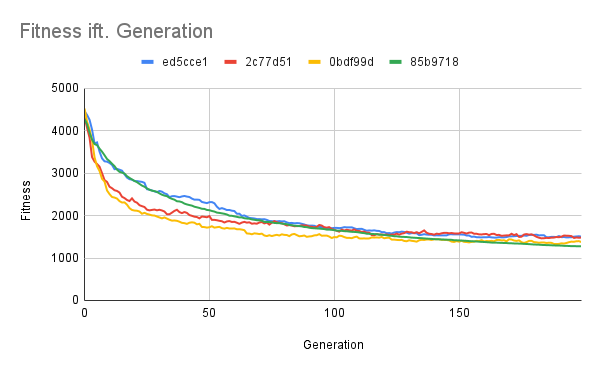

The beauty of genetic algorithms is there are so many things you can tweak: population size, selection rate, competition method, breeding mechanism, mutation strategies. I tried many different things and watched how it affected the fitness over time.

Here are some previous resuts, using different strategies:

Sometimes a strategy saw big gains early on, but leveled out and couldn’t get any better after 200 generations.

In the graph, you might notice that the green line has slower initial improvements, but moves down steadily, and by Generation 200 ends up being better than the others.

Sometimes i tried taking the best of previous runs, and cross-breeding them together, but that never worked. They were like different species at this point: they had developed entirely their own way of being the best in a totally different gene pool. It took a long time before their descendents became better than either ancestor, as they had to mix two totally different sets of DNA.

Bonus pictures

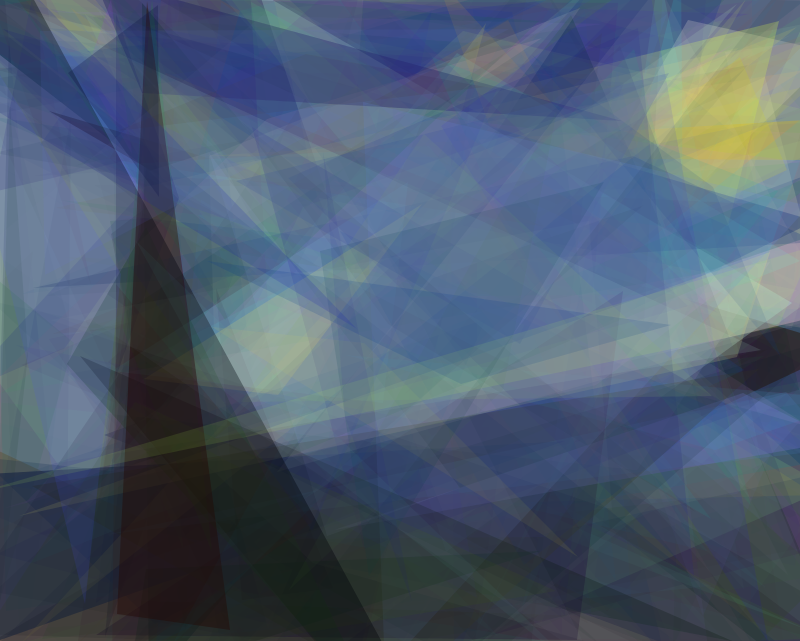

When doing something like this, it is customary to try a piece of classic art. I chose The Starry Night, by Vincent van Gogh.

The crossing triangles remind me of creases in a flag, so i decided to try the non-binary flag. Apparently, solid blocks of bold colours works really well for this. I’m delighted at how this one turned out!

Conclusion

I know the outcome is far from perfect, and i know other people have done similar things before, with much better results. But i had a lot of fun trying this, and i learned a lot about what genetic algorithms are, how to set them up, and how to tweak them.

Code

You can run your own pictures on your own computer, using the code from my GitHub repo here: github.com/aimeerivers/500triangles

Let me know if you make any cool pictures with it!

Any questions? Find me on Mastodon: @aimeerivers@queer.party